If you have been in higher education for more a while, you have probably encountered Bloom’s Taxonomy: Remember, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, Create. If you are new or need a quick refresh; review this brief primer.

The cognitive hierarchy that tells you whether you are asking students to think deeply or just recall facts.

Bloom’s is genuinely useful. But L. Dee Fink, in his 2013 book Creating Significant Learning Experiences, noticed something important. Bloom’s only addresses one dimension of how humans learn. It tells you how cognitively demanding a task is. It says almost nothing about whether students will care about it, connect it to anything real, or know how to keep learning on their own after the course ends.

For computing and STEM faculty specifically, this gap has real consequences. We spend enormous energy designing cognitively rigorous assessments and then wonder why students who passed the exam still struggle to function in an internship. Or why a technically strong student falls apart in a team environment. Or why a graduating senior freezes up when asked to learn a new framework on their own.

Bloom’s tells you how hard the thinking is. Fink’s tells you whether it matters to the person doing the thinking.

The Six Dimensions of Fink’s Taxonomy

Fink’s taxonomy is not a hierarchy. It is an interactive web where every dimension strengthens the others. Here is what each one looks like in the context of a computing or STEM course.

DimensionWhat It MeansIn a Computing CourseFoundational Knowledge (FK)Understanding and remembering key concepts, facts, and principlesData structures, algorithm analysis, language syntaxApplication (AP)Critical thinking, creative thinking, practical skills, managing projectsImplementing algorithms, debugging, system designIntegration (IN)Connecting ideas across subjects, disciplines, and life contextsSeeing how OS concepts relate to security; connecting theory to production codeHuman Dimension (HD)Learning about oneself and others, including identity, perspective, and collaborationCode review etiquette, equity in technical interviews, accessibility awarenessCaring (CA)Developing new feelings, interests, and values; becoming genuinely investedCaring about software quality, open-source ethics, end-user impactLearning How to Learn (LL)Metacognition, self-direction, and inquiry skills; becoming a self-improving practitionerReading documentation, developing a debugging mindset, knowing when to ask for help

Why This Matters Right Now

Here is the uncomfortable truth about generative AI and course design. AI is extraordinarily good at Foundational Knowledge. It can explain recursion, walk through a sorting algorithm, or produce syntactically correct code on demand. If your assessments primarily target FK, students do not need to engage with the material. They can simply delegate the work.

But AI cannot learn to care about software quality on your student’s behalf. It cannot develop their debugging mindset. It cannot give them the experience of genuinely connecting theory to a problem that matters to them personally. The upper dimensions of Fink’s taxonomy, specifically HD, CA, and LL, are exactly where human learning is irreplaceable. They are also exactly where most computing assessments underinvest.

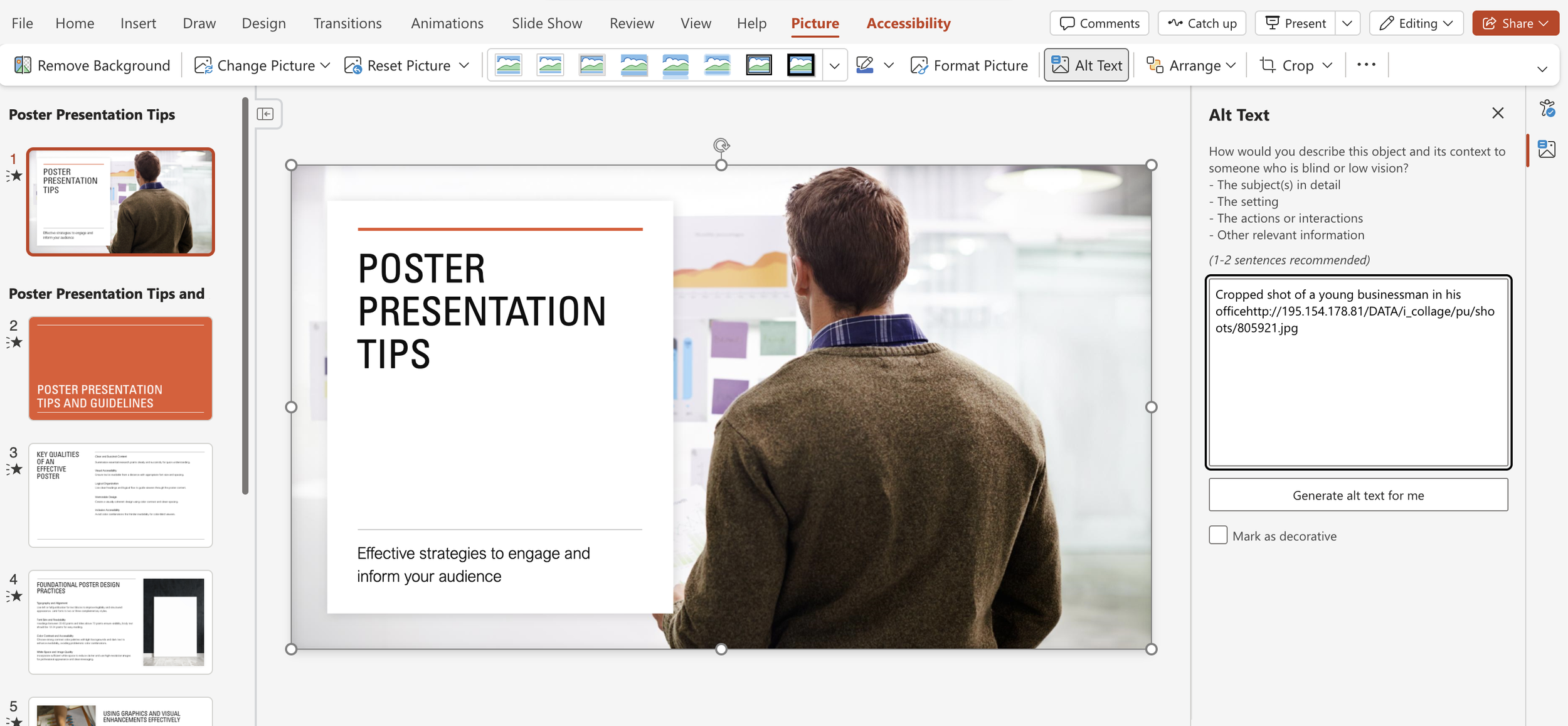

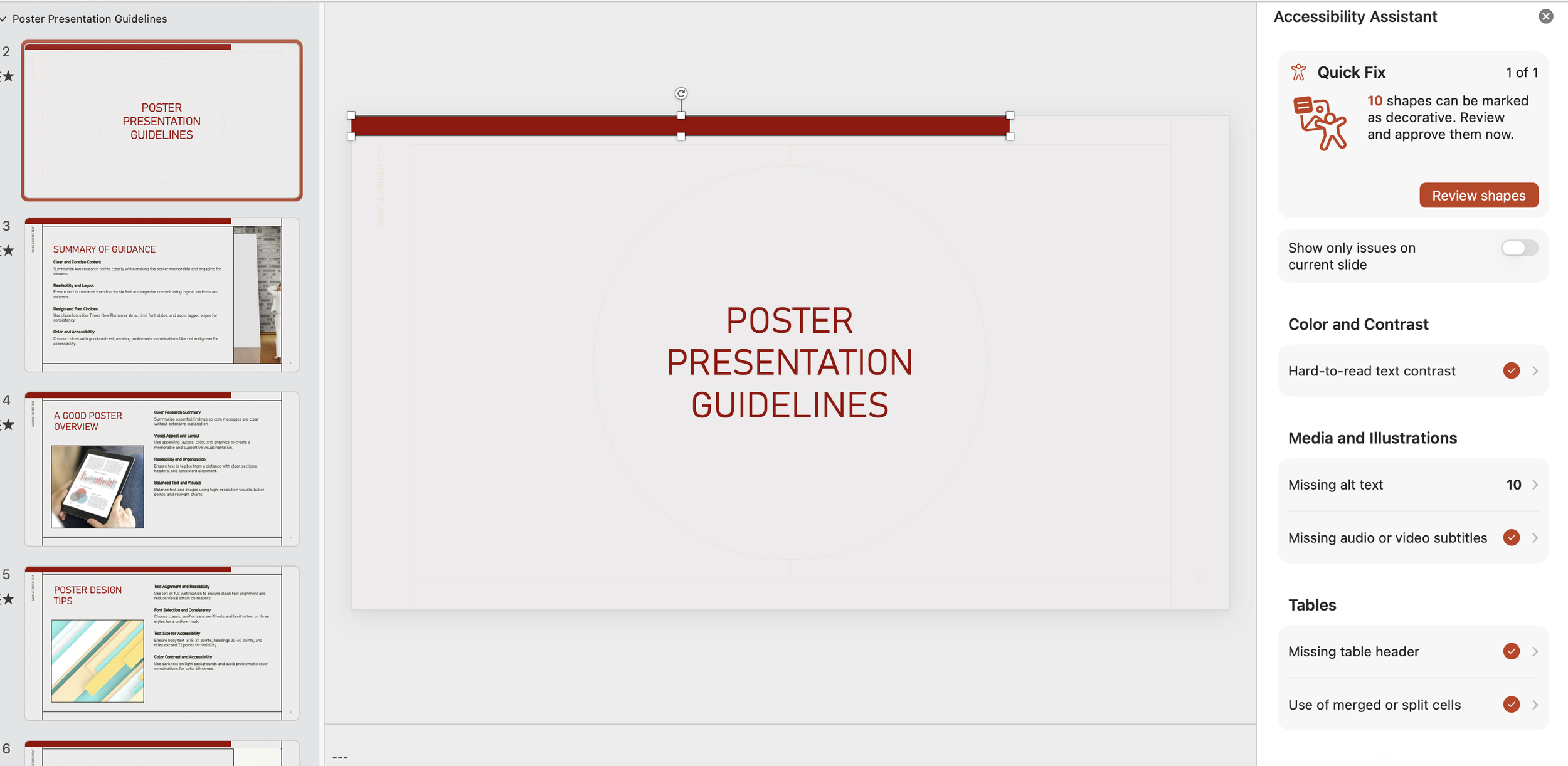

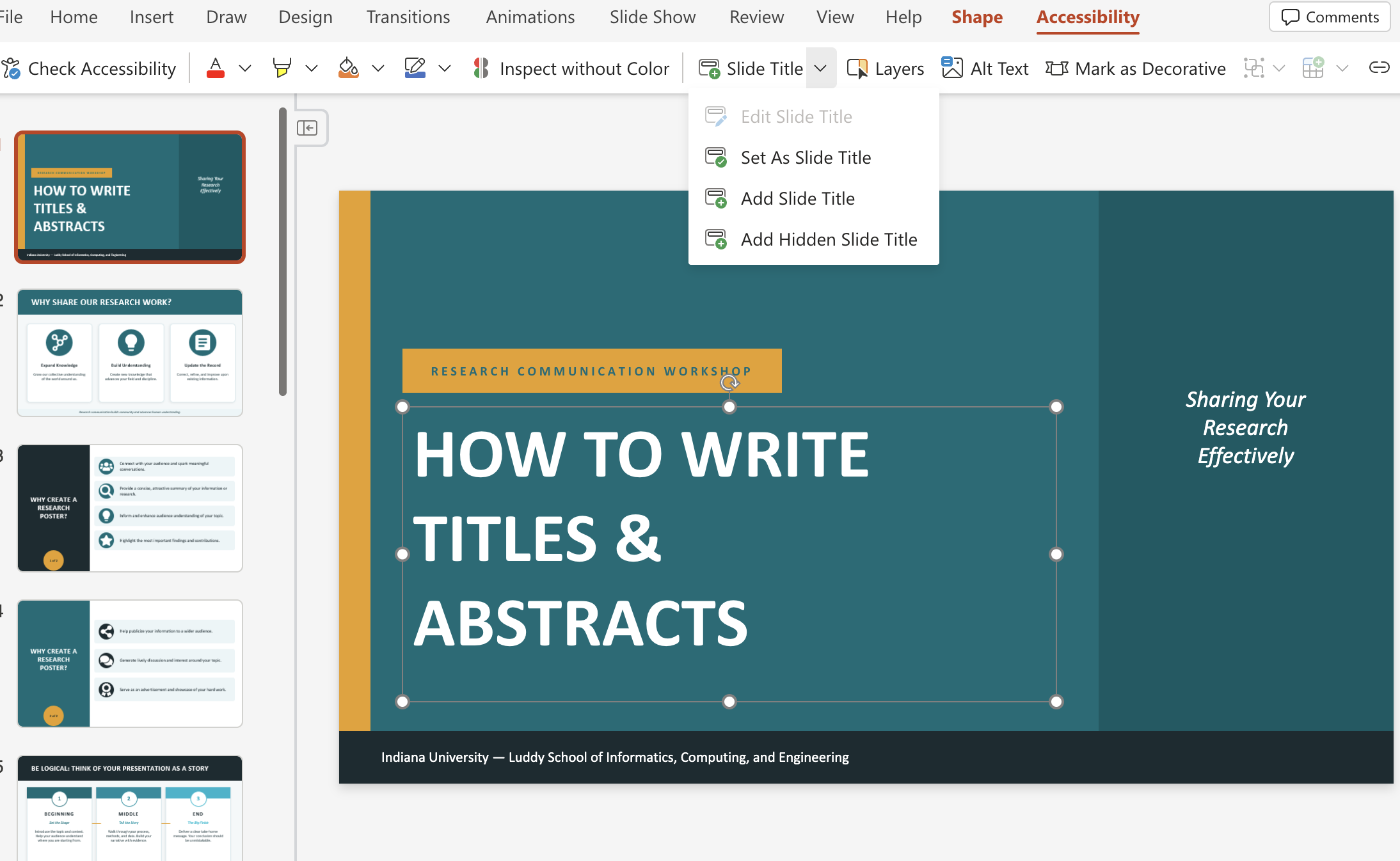

The AI Audit

For each of your major assessments, ask yourself: which Fink dimensions does this assignment actually require the student to engage? If you only see FK and AP, and especially if you only see FK, you have found your highest-risk assignment for AI substitution. That is your starting point for redesign. A good place to start is by auditing the verbs you are already using. The Computing Verb Atlas lets you search any verb and immediately see which Bloom’s level and Fink dimensions it activates, making the audit process much faster. [Open the tool.]

Practical Examples: Fink in a CS Course

The Difference One Question Makes

Consider a standard data structures assignment: “Implement a binary search tree with insert, delete, and search operations.”

This prompt targets Foundational Knowledge and Application. It misses Integration, Human Dimension, Caring, and Learning How to Learn entirely. It is also almost entirely delegatable to AI.

Now add one question: “Describe a real system you use daily that likely relies on a tree structure. How does your implementation compare to what you would expect in production? What surprised you?”

That one addition requires Integration (connecting BST theory to the real world), Human Dimension (drawing on the student’s own experience), Caring (investment in a system they actually use), and Learning How to Learn (comparing a learning exercise to production reality). AI can generate plausible-sounding text in response to that question. But the student still has to have had the experience to write something genuine.

Caring in a Systems Course

Caring does not mean students have to love your subject. Fink defines it as developing new interests, values, or feelings, including professional values. In a software engineering course, Caring might look like this: Does the student give any thought to writing readable code? Do they consider the next person who will maintain their work? Are they forming a genuine perspective on open-source licensing?

These are not soft skills. They are what separates a developer from a professional.

Learning How to Learn in Every Course

The LL dimension is the most underrepresented in computing curricula and arguably the most important one for long-term career success. The useful life of a specific technology stack is measured in years. The ability to independently pick up a new one is what sustains a career over decades.

What does LL look like as an assessment? It might be a reflection on which resources a student used to solve a difficult problem and why they chose those resources. It could be a post-mortem where students analyze their own debugging process. It can be as simple as asking students to document what they tried before asking for help, making their problem-solving process visible rather than just its final output.

The goal is not students who have learned your course. It is students who know how to keep learning after it ends.

A Note on Integration

Integration is the dimension most likely to shift how a student sees your discipline altogether. It is the moment when a student realizes that the graph algorithms from their CS course are the reason their navigation app works. Or that the ethics discussion in their intro course was not a detour but actually a preview of every technical decision they will make professionally.

Adding Integration to an assignment rarely requires a redesign. It often requires one additional prompt: “How does this connect to something outside this course?” The specificity of the answer will tell you more about a student’s genuine understanding than the code they submitted.

Getting Started: The Fink Audit

Before the next post, try this exercise. Take your next major assignment and map it against the six dimensions. Which dimensions does it genuinely require? Which are completely absent? Then ask yourself: what is the smallest possible change that would add one missing dimension without increasing your grading burden?

References

Anderson, L.W. and Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing. Longman.

ACM Committee for Computing Education in Community Colleges (CCECC). Bloom’s for Computing: Enhancing Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy with Verbs for Computing Disciplines (draft report).

Fink, L.D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences. Jossey-Bass.